Sheng Dai arrived in Atlanta just a week before classes began for the fall 2015 semester, and it was really a homecoming of sorts.

Dai is the newest faculty member in the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, arriving after two years at the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Energy Technology Laboratory. But before that, he spent half a decade in the School, earning his doctorate in civil engineering. He finished in 2013.

Dai took a few minutes recently to talk about his work and returning to a familiar place to start his career in academia.

|

Q: You were a Ph.D. student at Georgia Tech — what made you want to come back as a faculty member? |

|

|

|

A: I am thrilled coming back. The first day I started my graduate studies, it was very clear to me that I wanted to pursue [a career in] academia. I worked hard in terms of publishing, getting involved in teaching, writing proposals, and mentoring junior graduate students. I enjoyed exploring things in academia because of the freedom to realize what I want to know. It is that curiosity that drives me to stay in academia. … At the end of last year, there was an opening here at Georgia Tech. I said “Wow, that is a great opportunity.” I submitted my application package, because there is no other place more attractive than Georgia Tech to me. |

||

|

Q: What is it that makes this place so overwhelmingly attractive? |

|

|

|

A: Looking at all the [geosystems engineering] programs in the whole country, Georgia Tech has, on the one hand, so many faculty and, on the other hand, everybody working on different topics. Many visitors say, “Georgia Tech professors like to think out of the box.” Geosystems professors at Georgia Tech receive research funding from the new Engineering Research Center [created this summer], Department of Energy, U.S. Geological Survey, EPA, the petroleum industry, and many other funding agencies. And the good thing about Georgia Tech is really the good environment in the group. We get along well with each other. I spent five years here [as a graduate student], and I really love this department. |

||

|

Q: Has it been different these first few weeks being a professor versus being a graduate student? |

|

|

|

A: The biggest difference I think is, I actually know very little about academia. [laughs] I thought I knew a lot. So I’ll take the professorship itself as a research project. |

||

|

Q: You do a lot of work in energy and geoengineering. Why are you interested in that area? |

|

|

|

A: I gradually realized that energy is one of the biggest engineering challenges. All the national reports now are talking about energy, environment, water, education, disease, and infrastructure. But if we look at the reports from 10 years ago about the grand challenges or the big international challenges, energy was not on the top of the list. We are really in a period where our development is limited by having a secure and clean energy supply. Nowadays, for 70, 80 percent of our energy, we rely on fossil fuels —oil, coal and natural gas. These produce huge amounts of carbon dioxide. I realized that and thought I should contribute a little bit on this topic of energy and carbon. |

|

Q: When we talk about what you hope to accomplish with your work, is it new sources of energy? Is it dealing with the carbon we’re already producing? Is it something else? |

|

|

|

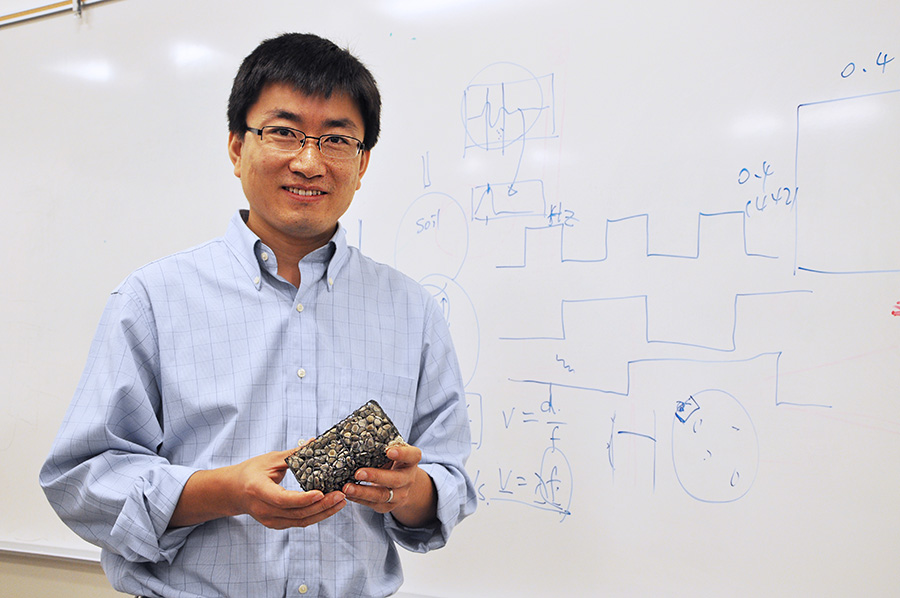

A: Gas hydrate could potentially be a new energy source and cleaner than coal; but it is [frozen] methane, also a fossil fuel. The methane trapped in hydrates has a huge amount of energy: The rough estimate is that the total amount of carbon trapped in methane gas hydrate would be four times the total amount of carbon trapped in current conventional natural gas, coal and oil. … So that is a big resource, but this is still fossil fuels. In terms of cleaner energy, we think of nuclear, wind, geothermal, solar. … Geothermal energy is the one that is most relevant to geotechnical engineers. So far, we have used only shallow geothermal for room cooling and heating. There is another concept called Enhanced Geothermal Energy Recovery. Basically, we drill two wells down to the ground using cold water, because it is so hot under the ground — to a temperature like 200-300 degrees Celsius — the cold water will suck up all the heat and come out as a vapor, and this vapor will turn a turbine and generate electricity. This is for large-scale electricity generation of geothermal energy. It has not been commercialized yet, because we still have lots of unknowns. … It is really cool, because it’s carbon free. For a small college town, probably one or two of these production wells can satisfy the electricity demand there. |

||

|

Q: In other words, you have a whole lifetime of questions that you can be working on. |

|

|

|

A: Yes, energy is a big part. The other part is the carbon. In 2013, the United States pumped about 5.2 gigatons of carbon into the atmosphere. If we compare the total weight of carbon we produced to the African elephant — which is around 5,000 kilograms each — we pumped around 1 billion elephants of carbon into the air. So carbon is a huge issue. Our current CO2 concentration in the air is around 400 ppm. [The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] says the tipping point may be 470 ppm. We can easily be there in 20-30 years, but actually, we don’t exactly know the tipping point. That is why I also work on carbon sequestration. The idea is to capture the carbon from power plants, and then inject it into the deep underground or into the oceans too. … That is the only solution we have so far that can kill large amounts of carbon. There are so many exciting things we can do to help mitigate our energy and carbon situations. One of the great things about Georgia Tech civil engineering is, the professors are working on projects that directly have an impact on human life and our society. |

||

|

Q: Is that why you wanted to be a civil engineer or a geotechnical engineer? |

|

|

|

A: I love geotechnical engineering the most because it studies the underground, the ground that we are standing on. It may not be as fancy as putting up a structure above ground that is beautiful, but underground there are so many things we don’t know. It is so challenging. |